The ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland began in the 1960’s, and ended in 1988 with the Good Friday Agreement. In the interim, there were hundreds of civilian and military deaths on both sides. The resolution of the conflict (called “The Troubles”) included various civil uprisings by various political and paramilitary factions. The conflict ended with a peaceful agreement on both sides. Here, we explore some failed attempts at resolution, leading up to the Good Friday Agreement. Part 2 of 3.

Attempts at Resolution

Direct rule by the British was supposed to serve as a short term measure, and the process was ultimately designed to restore self-rule to Northern Ireland. The first major attempt in shifting the power paradigm was in the 1973 Sunningdale agreement, which provided the framework for a power-sharing administration. This moved theoretically would have allowed a role for Irish Nationals to participate in the internal affairs of Northern Ireland- dubbed the “Irish Dimension”.

The British government introduced the measure to parliament. However, only three nationalist parties participated in the talks, while representatives of the “extremes” were unwelcome. This move infuriated many political parties, who were grouped into “anti-unionist parties”. Although the talks ultimately failed, Sunningdale was said to be the framework for the successful Good Friday agreement nearly 25 years later.

As post-Sunningdale violence escalated, successive UK governments ensured that any parties involved in the forthcoming peace process were legitimate and non-

violent. The 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement was yet another serious attempt to resolve “The Irish Question,” giving the Irish an advisory role in affairs and stating that there would be no constitutional change (or unification) without the consent of the Irish people. The proposal for a power-sharing government was rejected and alienated the unionist community.

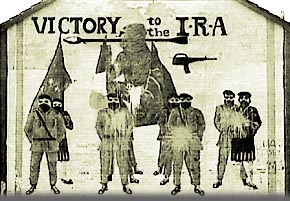

The Irish Republican Army faced a series of splits and factions since the 1920’s; the Provisional IRA, which emerged in December of 1969, was the biggest and most active paramilitary group that participated in The Troubles. The organization was designated unlawful and a terrorist organization in the UK, and an unlawful organization in Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the IRA focused their efforts on the defense of Catholic areas, and began an offensive campaign in 1971.

Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA, were opposed to the agreement. By the late 1970’s, the party had grown in popularity and prominence. The election of a republican hunger striker Bobby Sands showed the party that political involvement proved effective. After Sands’ death in 1981, Sinn Fein adopted the “the armalite and the ballot box” strategy, enveloping both political and armed struggles against the British. Here, the IRA continued the armed struggle while Sinn Fein fought on the grounds of political change.

The IRA’s announcement of a ceasefire in 1994 began the successful peace process across the factions to end ‘The Troubles”.